Dorset nature notes

Geology and Landscape

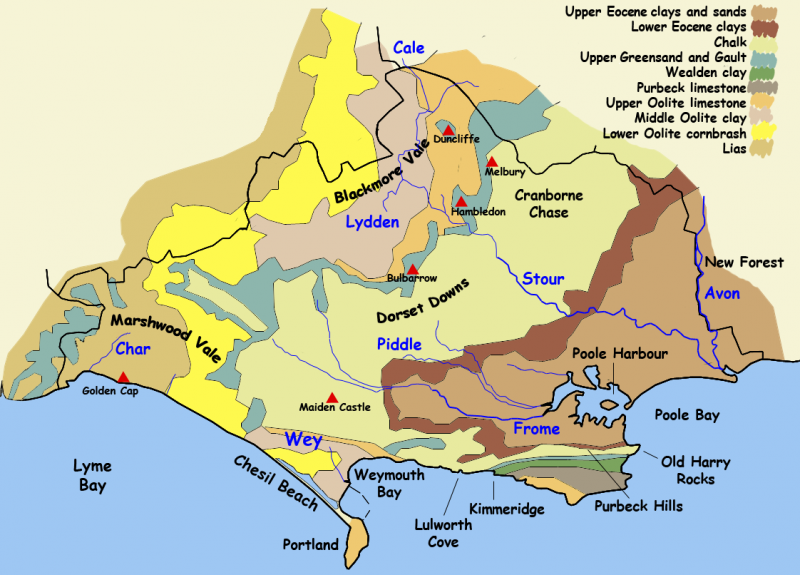

The complex geology of Dorset gives rise to an extraordinary range of landscapes and habitats, which in turn are home to a diverse population of wildlife. The county can be divided up into 5 broad divisions based on its geological characteristics:-

- Limestone plateau of the Isle of Purbeck and Portland

- Upper and Lower Eocene clays and sand which underlie the heathlands of south east Dorset

- Chalk and oolitic limestone which form the rolling Doset Downs stretching in a wide sweep across the centre of the county

- Heavy oolitic clays of the Blackmore Vale in the north west

- Complex limestone and sandstone hills divided by clay vales in the west, such as the Marshwood Vale.

Simplified Map of Dorset Geology (Copyright)

Most of the Dorset 100 route lies within the areas of chalk downland, the heathlands, and the Marshwood Vale. The contrasting landscapes reflect the differences in underlying geology. Flat, forested heaths give way to rolling chalk hills, and, further west, the route reaches the dramatic summits of Pilsdon Pen (277m) and Lewesdon Hill (279m), the highest points of Dorset, These greensand hills lie in the remote and beautiful Marshwood Vale. They are topped by iron age forts, sites of ancient settlement in the area. As the route turns east you return to the chalklands and reach Eggardon Hill (247m) and then a backward loop leads to the summit of the boat-shaped Shipton Hill(170m), the cap of which is formed of greensand.

While the underlying geology dictates the broad nature of the Dorset landscape, it is the influence of Man, who, in using it for his own ends, has created the landscapes we see today. Farming, forestry, and grazing has resulted in an interesting mosaic of different habitats. For example, the water meadows of the Piddle and Frome, grazed by sheep over the centuries, used to be deliberately flooded to encourage early growth of grass by means of a complex system of ridges and channels controlled by hatches. These meadows are sites of one of the earliest and best centres of such water meadow technology, and you can still see evidence of it today.

Flora

These notes can only touch the surface regarding the many plant species that can be found in Dorset’s different habitats. The most florally prolific of these habitats is the unimproved chalk grassland. Owing to the poor soil quality, no individual species is able to dominate the sward. Flowering in May alongside cowslips may be such gems as early gentians, early purple orchids, chalk milkwort, and fairy flax. The steep-sided ditches of prehistoric earthworks are particularly good places to find these, e.g. on Eggardon Hill. In contrast, the ramparts of Pilsdon Pen, which overlie acidic greensand, are covered by heather and bilberry, and the lower slopes dominated by bracken, bluebells and tormentil. Lewesdon Hill is unusual in being cloaked by trees.

Dorset’s heathlands are considered to be internationally important because of the present day scarcity of this type of habitat. Plants here are adapted to survive on dry and wet heath, bogs, and rivers. Heather is dominant, and seems sometimes monotonous, but it is the food plant for the caterpillars of over 55 moths and butterflies – a veritable larder for insect-eating birds like the Dartford warbler.

The route also passes through ancient woodlands where woodland specialists such as opposite-leaved golden saxifrage and the diminutive moschatel may be seen as well as some lingering bluebells. The verges of narrow lanes should give close views of red campion, garlic mustard, early purple orchid, and greater stitchwort. Dorset has some of the best and most spectacular holloways in Britain, home to damp-loving species of fern, and the route follows such a holloway after leaving Loders.

River banks are habitat to waterside plants such as the yellow flag iris, greater willow herb, purple loosestrife, and water forget-me-not, but it is unlikely that these will be yet in flower when the Dorset 100 takes place.

Look out for veteran trees. The famous Tolpuddle Martyrs Tree, a sycamore, is over 300 years old. Its crown is pruned on a regular basis, to prolong the tree’s life. It is expected to live another 200 years.

Dorset is fortunate (from the naturalist’s point of view) in lacking large conurbations and industry. Westerly prevailing winds mean that the county has very low levels of air pollution, which favours the growth of interesting mosses and lichens. These can be best seen on the walls and gravestones of rural churches.

Butterflies and Birds

Owing to its mild climate and wide variety of habitats, Dorset hosts more butterfly species than does any other English county. Late May is a particularly good time to observe butterfllies. As well as the more common species look out for specialists such as the brightly-coloured Adonis blue which thrives in sheltered patches of downland, and the brick-patterned wall brown sunning itself on bare patches of ground – and on walls! Vivid green hairstreaks inhabit the edges of scrub, and, where the hillsides are still carpeted by cowslips, the rare Duke of Burgundy may make an appearance.

The rural nature of Dorset and lack of human disturbance also benefits birds. These are more adaptable to varying environments than are butterflies, their distribution depending mainly on the availability of food. In winter, resident species may eat seeds and berries, but in the summer all birds rely on a good supply of insects and caterpillars to feed their young. For example, swallows and martins take advantage of the bonanza of caddisflies emerging from the rivers in May. Look out for them swooping over water courses, and also for birds associated with rivers such as grey wagtails. These bobbing birds eat water insects and often nest under bridges. The colourful kingfisher may also be spotted. The hedges of the open countryside are homes to many different birds including the yellowhammer, whitethroat, linnet, goldfinch, stonechat, and tits. Green woodpeckers are associated with the anthills present on undisturbed downland. Listen for the distinctive call of the cuckoo, and the everlasting song of the skylark, a bird now sadly in decline. Buzzards and ravens, on the other hand, are doing well. On hilly ground look up to see a broad-winged bird floating in the thermals, whilst a sharp croak or bark indicates the presence of a raven.

And finally . .

Almost all of what has been described may be encountered on the Dorset 100 route. The most important thing is to be aware and look around you as you walk. So enjoy all that our wonderful county has to offer!